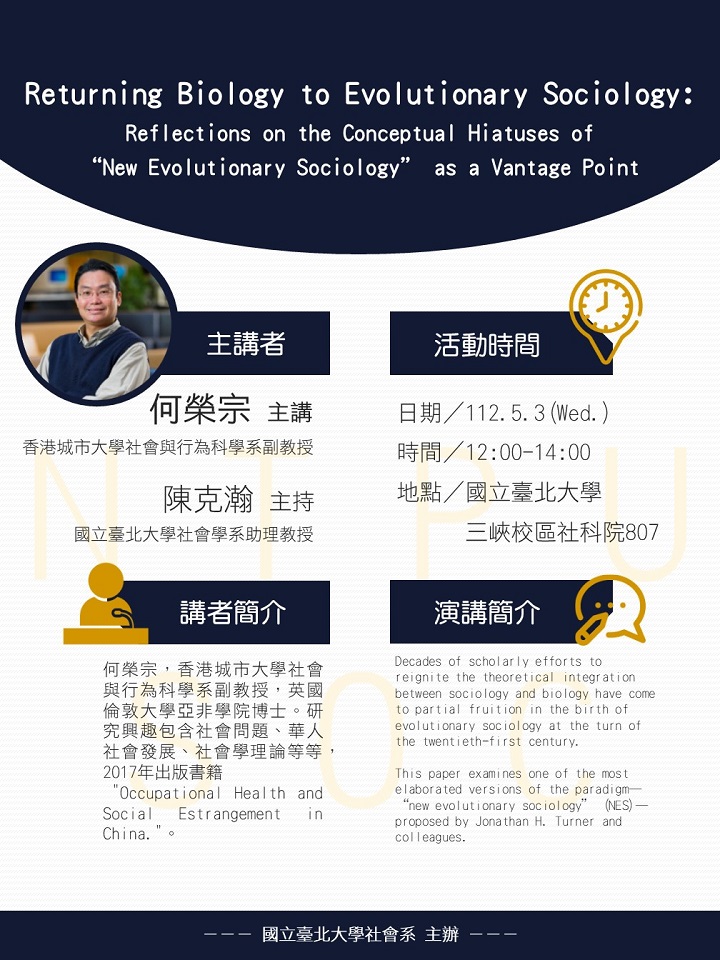

Decades of scholarly efforts to reignite the theoretical integration between sociology and biology have come to partial fruition in the birth of evolutionary sociology at the turn of the twentieth-first century. This paper examines one of the most elaborated versions of the paradigm—“new evolutionary sociology” (NES)—proposed by Jonathan H. Turner and colleagues. NES emphasizes purposeful, multilevel selective pressure targeted at corporate units, groups, or societies—rather than the blind, Darwinian natural selection on individuals—from which institutional systems are developed. Despite its contribution, NES possesses conceptual lacunae that have fettered NES in specific and evolutionary sociology in general from becoming a novel and truly evolutionary-cum-sociological paradigm in explaining social phenomena. This paper identifies three conceptual hiatuses of NES, in that it lacks due deliberation of (1) the gene-culture interaction that bridges individual behaviors—via natural, sexual, group, and multilevel selections—with the emerging sociocultural formations; (2) the epistemic role of fitness as a post factum propensity in empirical analysis; and (3) the concept of causal mechanism utilized to explain the diverse paths leading to the emergent phenomena.